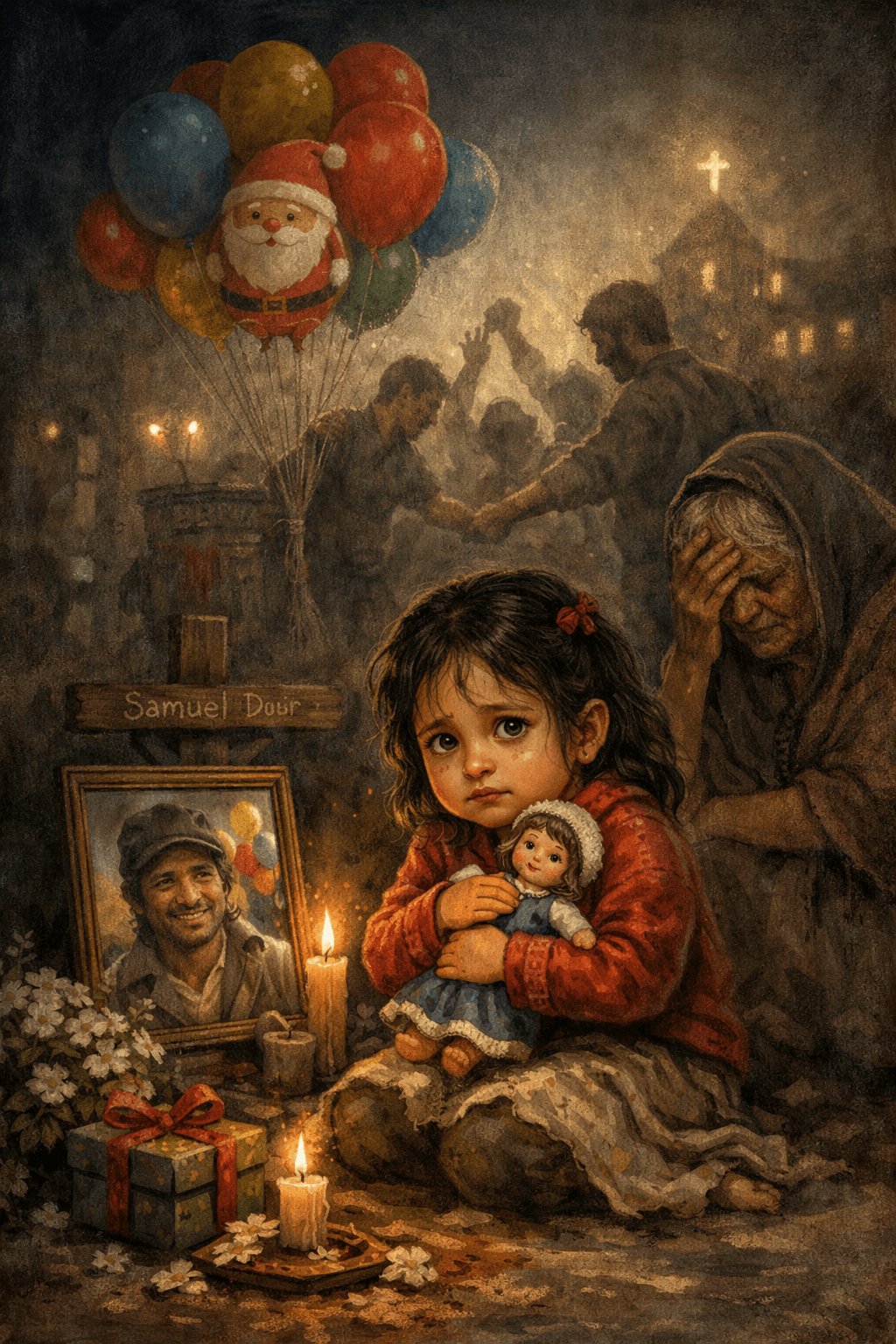

No one in the neighbourhood remembered the first time they saw Samuel Das selling balloons, but everyone remembered the morning his body was lifted from the roadside like a broken doll, his colours scattered, his breath gone. Until that day, he had been simply Sammy—the balloon-seller who walked along the pavements of Old Park Street, humming Christmas carols all year long, even in the burning April heat when the rest of the city forgot winter existed. His smile was as familiar as the red plastic bucket that held the balloons tied in neat bundles—sun, moon, Santa, stars—floating like little dreams waiting to be bought.

For three-year-old Maria, he was simply Papa. And she was the only dream he truly lived for.

Every morning he would wake before dawn, measure out two palmfuls of rice carefully from the jar, making sure there was just enough for lunch and dinner, and then quietly sing to the half-asleep child curled beside him. Their house was hardly more than a tin shed at the edge of the slum, with two small pots, a cracked bowl, and a calendar from last year hanging crookedly on a nail. But Samuel believed it was a palace. Because Maria was there.

“Just a few days left for Christmas,” he whispered to himself that December morning, rubbing sleep from his eyes. “My Maria will get her gift this time, no matter what.”

For months he had been saving, dropping his coins into an empty cough-syrup bottle. It was not much, never enough. Life swallowed money faster than he earned it. The rent took a bite. Medicine for his ailing mother took another. Food took most. But he had still saved thirty-seven rupees and sixty paise. Enough, he thought, to buy the small wooden doll Maria had pointed at from across a shop window on Park Street.

“Papa, she looks like Aunty Mary from the church!” she had squealed, her eyes shining.

“That is your Christmas gift,” he had promised.

He had never broken a promise to her. Not once. Not even when it required going hungry.

That morning, the sky was misty with winter fog, and the city was preparing for festivities. Fairy lights were already draped across the streets. The shops smelled of cinnamon and fresh bread. A choir was singing somewhere far away. Samuel felt hopeful, almost cheerful, as he walked with his balloon bucket. He hummed “Silent Night,” the one song he knew by heart.

But the city had become unpredictable in recent years—angry, impatient, quick to burn and quicker to hate. Rumours spread like forest fires. Mobs started from nothing—one word, one suspicion, one misunderstanding. And on the morning of December 23rd, a misunderstanding was waiting for Samuel like a trap.

It began near the marketplace. A wallet was stolen from a man who was already furious at losing money before the holidays. Someone shouted, pointing at the first unfamiliar face he saw—Samuel, walking past with his balloons.

“That’s him! Catch the thief!”

People turned. Samuel froze, confused.

“Not me… I didn’t…”

But the crowd was faster than his words. The balloon seller with his brightly coloured cargo seemed an easy target. People who had never looked him in the eye when he sold balloons suddenly found energy in their arms and stones in their fists. Someone grabbed his collar. Someone slapped him. Someone knocked him to the ground. The chorus of accusations grew like thunder—“Thief! Thief! Beat him!”

“No! Please! I didn’t take anything!” Samuel cried, trying to protect his head.

His balloons floated away, free at last, drifting above the chaos as if ashamed of the brutality below. The crowd grew into a monstrous shape—dozens of hands, dozens of feet, crushing the man who had never harmed anyone.

He tried to speak Maria’s name, but his voice drowned under the roar of the mob.

“Hit him harder!”

“Teach him a lesson!”

His limbs twisted. His breath scattered. His vision blurred. In his final moments, he tried to think of his daughter’s Christmas gift. Thirty-seven rupees and sixty paise. A wooden doll. A promise.

He never stood up again.

When the police finally dispersed the crowd, the real thief had already fled. The wallet was found later in a gutter. But the knowledge arrived too late. Samuel lay on the cold ground, his body still, his smile gone forever.

Maria waited the whole day for her father. She sat on the doorstep of their tin house, humming a half-remembered Christmas tune. Every now and then she peered down the narrow lane, expecting to see him walking toward her with the red bucket and the balloons dancing behind him.

“Papa coming,” she told her grandmother confidently. “Papa bringing gift.”

Her grandmother, old and frail, stared at her with eyes that had seen too much sorrow already. A neighbour had come running hours earlier, breathless, holding nothing but grief in his trembling hands.

“They killed him,” the neighbour whispered. “They beat him to death in the market.”

The old woman had felt everything collapse at once—her legs, her breath, her voice. She wanted to scream, but no sound came out. She wanted to protect the child from the news, but she did not know how.

Maria tugged her grandmother’s saree. “Nani, Papa late. Why Papa late?”

The grandmother wiped tears secretly with the end of her saree.

“He… he will come later,” she replied. “Let’s light a candle for him.”

But Maria shook her head. “Papa will light. Papa always light.”

The night grew darker. The street outside glowed with Christmas lights, each twinkle mocking the darkness inside the small house. The choir from the nearby church sang carols, but the notes felt heavy, as though burdened by the unspoken tragedy that had unfolded.

The grandmother kept pacing the room, wringing her hands.

Finally, there was a knock on the door. Maria jumped up. “Papa!”

But it was not Samuel. Two police constables stood outside, their faces stern but softened with guilt. Behind them stood a social worker from the local mission.

“We are sorry,” one of them said. “Your son… we found him. It was a mob lynching. He is no more.”

The grandmother collapsed to the floor with a wail that tore through the stillness of the night. Maria clung to the doorframe, watching the scene with puzzled eyes.

“No more? What is no more?” she asked, her voice trembling but innocent.

The adults could not answer. Words felt too cruel.

The next morning, the priest from the church arranged a small funeral. Only a few neighbours came, whispering among themselves. Some shook their heads helplessly. Some blamed fate. No one admitted their silence, their complicity, their cowardice.

Maria stood near the coffin, holding her grandmother’s hand. She looked at her father’s still face, trying to make sense of why he wasn’t smiling at her. She touched his cheek.

“Papa cold,” she said softly. “Papa sleeping?”

Her grandmother cried harder.

The coffin was lowered into the ground. The priest sprinkled holy water. The choir sang “Silent Night.”

But for Maria, nothing made sense.

Where was her doll? Her gift? Her father’s warm voice? His gentle laugh? Why had he not returned?

She sat beside the grave long after the others left, staring at the freshly piled earth.

“Papa,” she whispered, “I wait. I wait for gift.”

Life after Samuel’s death turned into a slow, merciless struggle. The grandmother tried to earn by washing utensils in the nearby houses, but her strength failed often. Hunger became a frequent visitor. The rent collector knocked every week. The landlord threatened eviction. Maria grew quieter, her eyes losing the sparkle they once had. On Christmas morning, when other children ran about with toys and sweet cakes, Maria wandered the street barefoot, searching for something she could not name. When she returned home, the grandmother was weeping silently. She had nothing to give the child—not food, not money, not hope.A soft knock came at the door. It was the young missionary woman who had helped during Samuel’s funeral. She held a small paper bag.

“I thought Maria might like this,” she said. Inside was a wooden doll—simple, painted with care, its face smiling gently. The very doll Samuel had wanted to buy.Maria’s eyes widened. She touched the doll reverently, then clutched it to her chest.

“Papa send?” she asked.

The social worker bit her lip, then nodded. “Yes, Maria. He wanted you to have it.”

The child smiled for the first time in days, though her eyes still glistened with questions she was too young to ask.

She ran outside to show the doll to the sky.

“Papa gave me gift,” she whispered. “See, Papa! I have it now.”

The grandmother stood by the doorway, wiping her tears. The city around them went about its celebrations, loud and bright, unaware of the small fragment of joy salvaged from an ocean of grief.

Yet the doll, for all its beauty, could not fill the void Samuel left behind. Maria hugged it tightly every night, as though it carried her father’s last breath.But she would grow up knowing the truth—that her father had been an honest man killed by a cruel crowd that mistook violence for justice. She would grow up remembering a face frozen in stillness rather than laughter. She would grow up carrying a grief too large for her tiny hands.

Years later, when she would be older and read in newspapers about yet another mob, another victim, another unnecessary death, she would tremble. Because the world had stolen something from her long before she understood what mobs were or how hatred worked.They had stolen her father. They had stolen her Christmas. They had stolen her childhood.But they could not steal the memory of a man who sold dreams in the shape of balloons, who loved his daughter more than his own life, who saved every coin he could for a single promise.

Samuel’s story remained alive in the small house on the edge of the slum, carried by a grandmother’s fragile heart and a little girl’s wooden doll.

And every Christmas, Maria placed the doll beside a candle and whispered to the night sky:

“Papa, I still have your gift. And I still love you.” Because love, unlike mobs, never dies.

International Tagore Awardee writer Dr. Ratan Bhattacharjee is a former Affiliate Faculty Virginia Commonwealth University& Ex Associate Professor and Head Post Graduate Dept of English Dum Dum Motijheel College, President Kolkata Indian American Society & Columnist for national Dailies